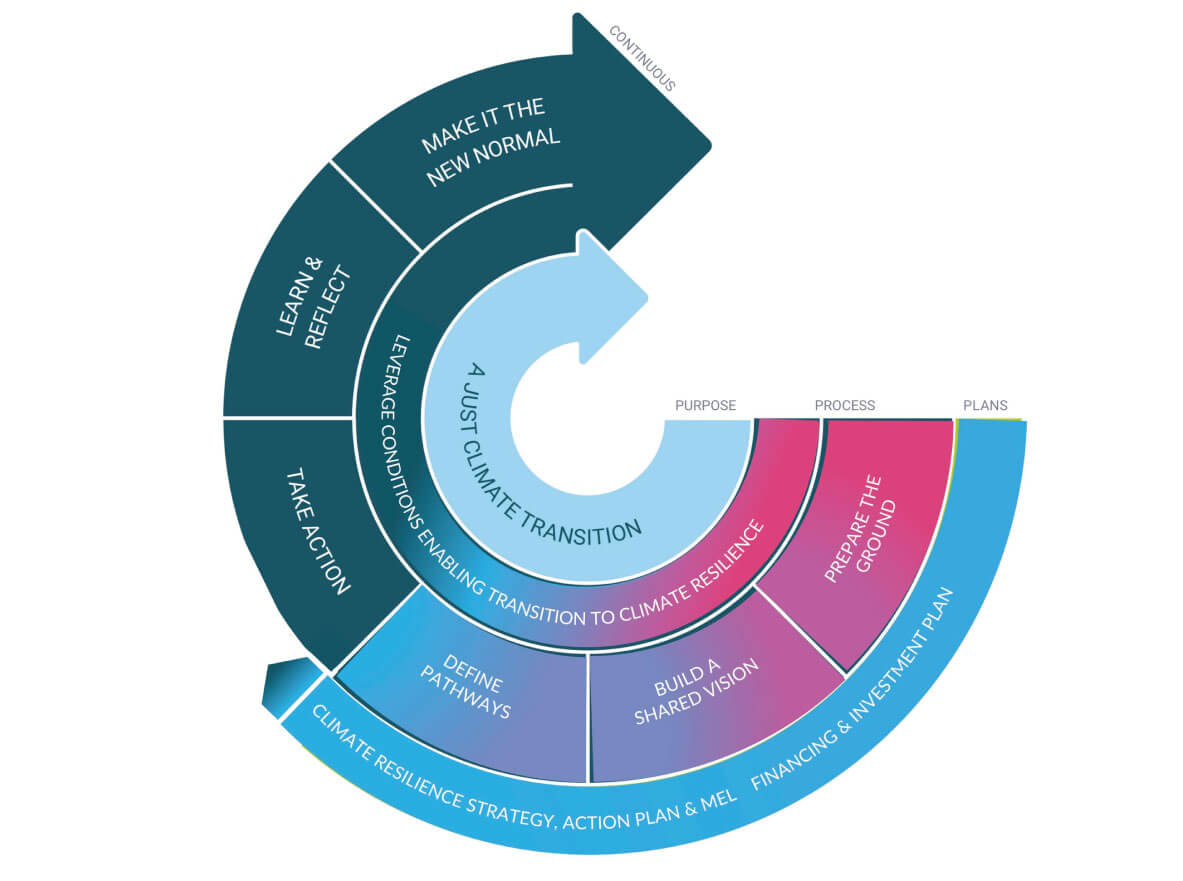

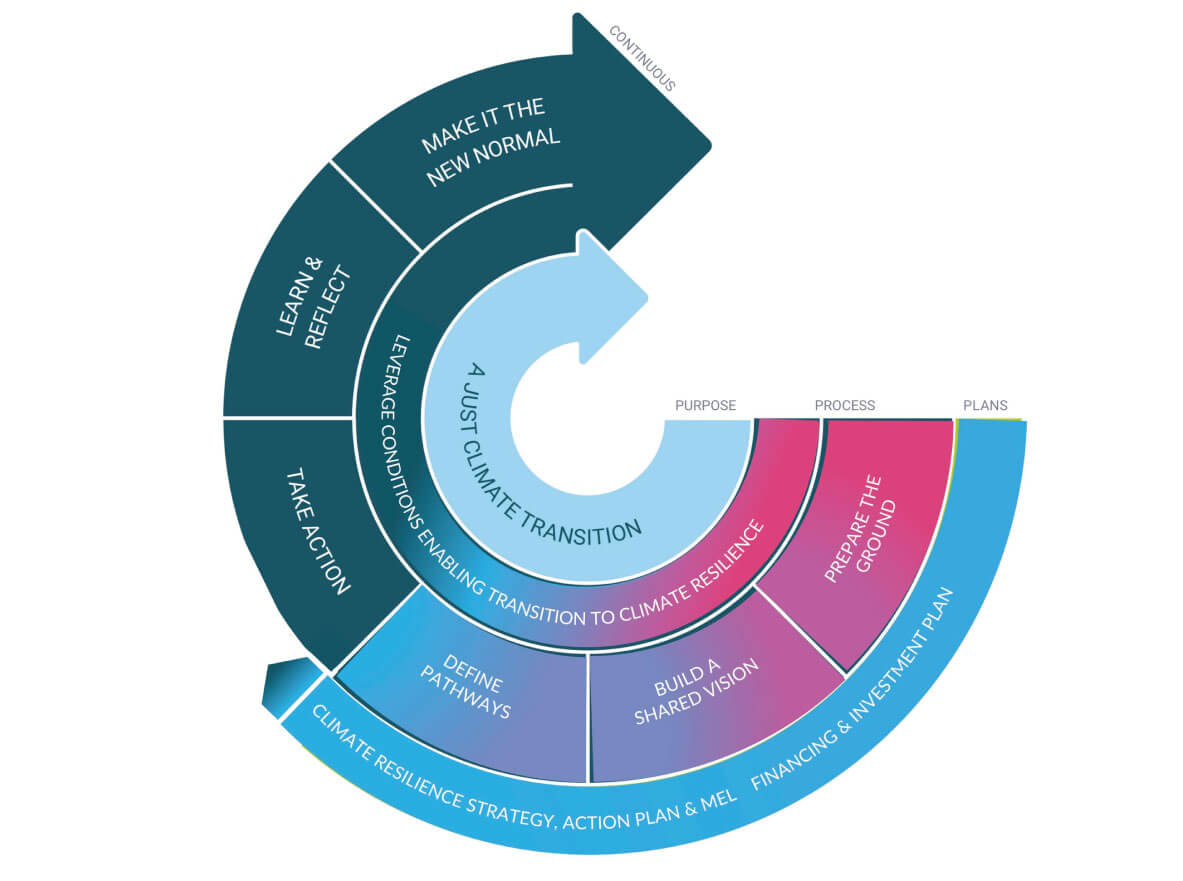

What is this journey about

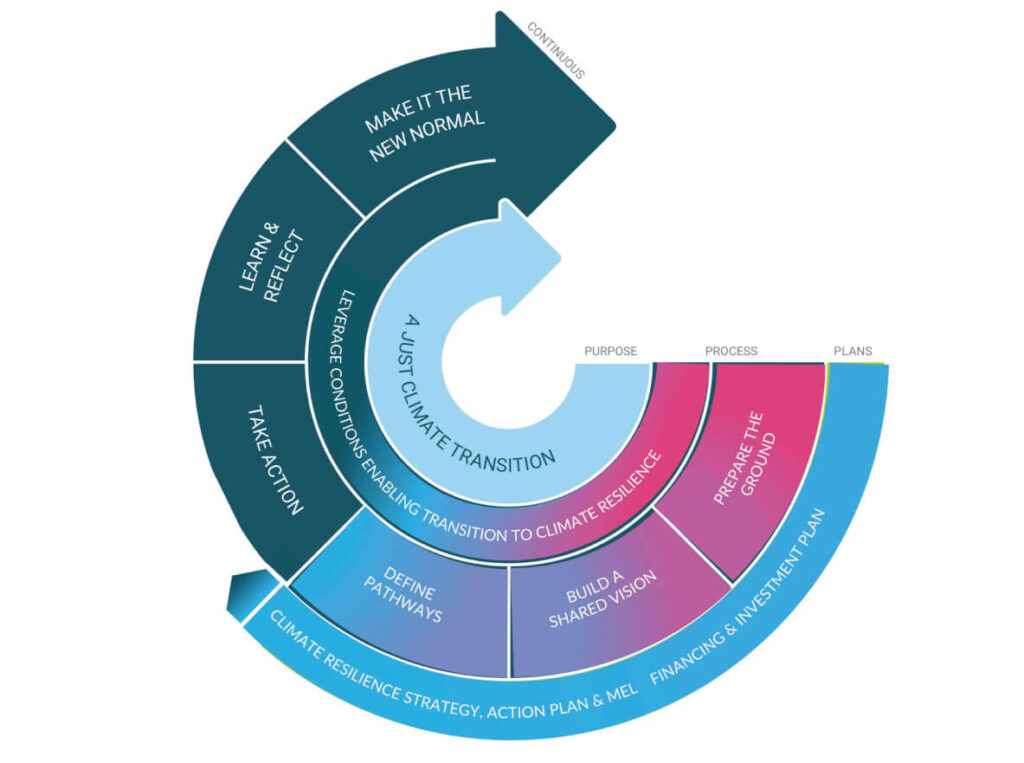

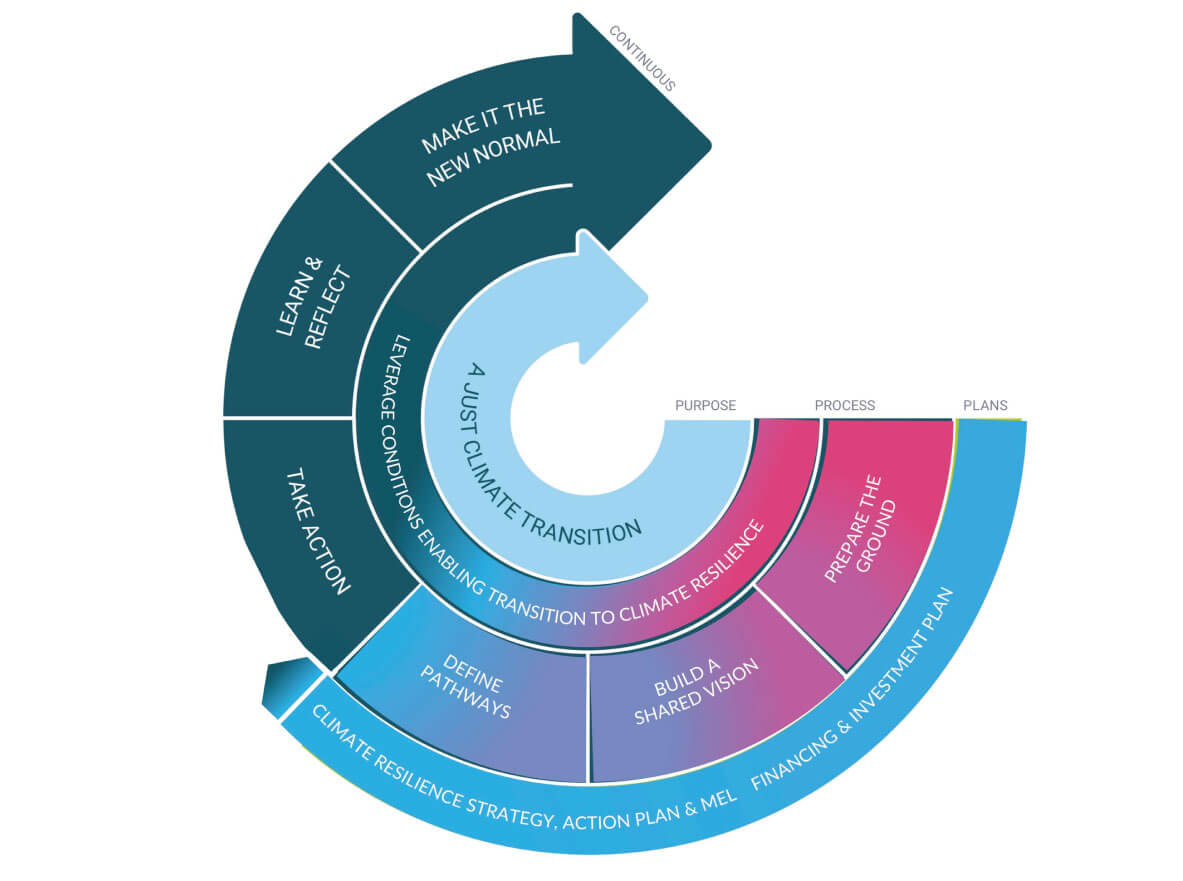

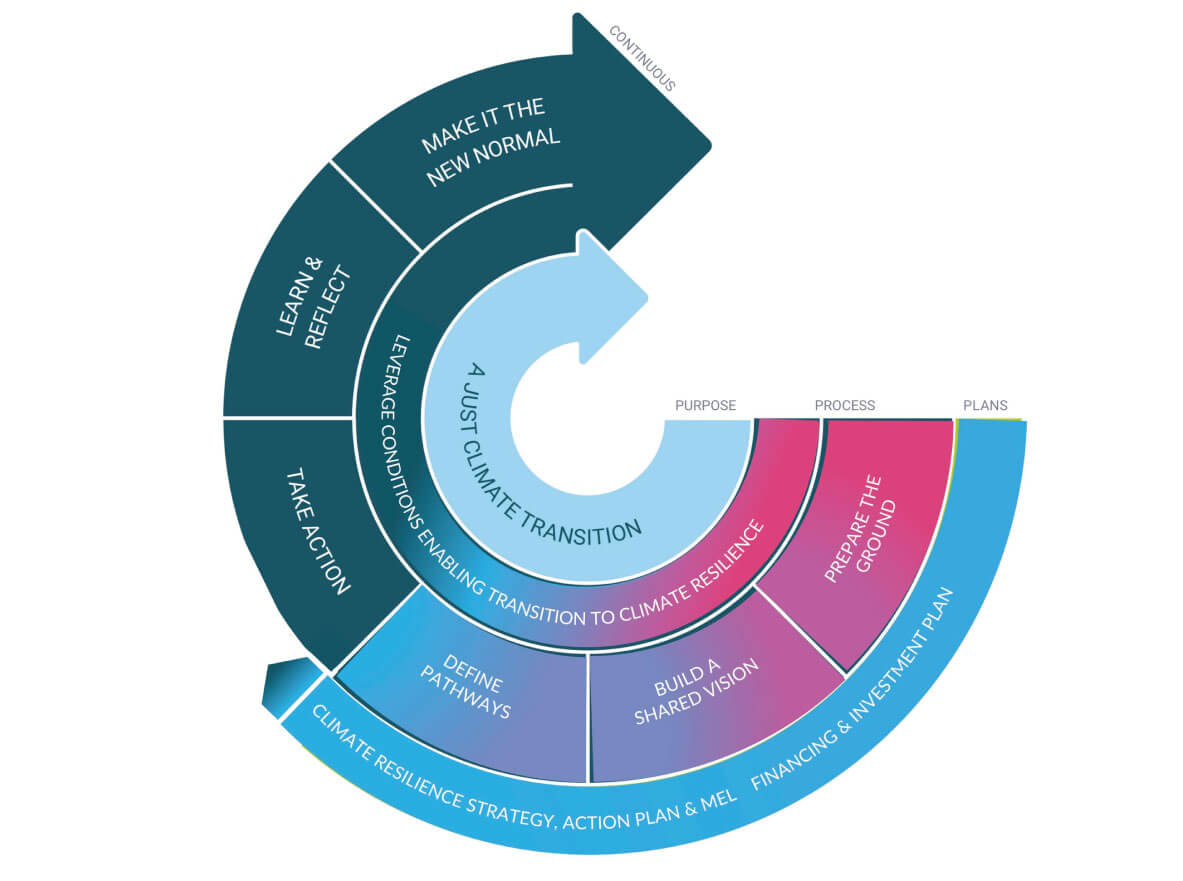

The Regional Resilience Journey (RRJ) is an adaptable framework for regions and communities that wish to transition to climate resilience through a transformational adaptation approach. It helps regions to flourish in their future climates, by moving beyond reactive and incremental adaptation of existing systems. Instead, it seeks to bring about systems change where this needed to close the adaptation gap and deliver long-term prosperity in the face of climate change.

The framework provides step-by-step guidance, a set of activities, tools and milestones that allows regions at all maturity levels to either produce their first climate resilience plans and intervention portfolios or to improve the existing ones by applying a systemic approach, just transition principles and by harnessing transformative innovation.

Pathways for climate adaptation and transitioning to climate resilience bring together interventions across multiple levers of change in a coherent portfolio of actions, outlining how each intervention contributes to progress towards the desired pathway.

This means that the framework takes into consideration complex regional scenarios and fosters an integrated work on different enabling conditions to maximise institutional, socialsocial, and financial powers. Acknowledging the inter-connectiveness of different fields of work, the transformative perspective aims to look beyond climate adaptation and to identify synergies with related sectors, while also strengthening collaboration and multilevel and multistakeholder engagement.

A systemic approach to accelerating climate resilience

Aiming at transformational adaptation the RRJ inherently supports a systemic or systems approach, which, instead of breaking down the complexities of climate resilience to be considered as separated parts, encourages to understand and address this complexity with all its relevant parts and relationships in its entirety. Such systemic approach allows regions and communities to more intentionally frame interventions towards a desirable future, taking into account leverage points and stakeholder perspectives, balancing disaster risk reduction with long-term prevention and adaptation, and to avoid maladaptation.

The RRJ uses a whole-of-government and multi-level governance approach to support regions in work beyond departmental siloes, supports meaningful engagement of stakeholders across all relevant stages of the journey, and requires an underpinning transdisciplinary knowledge and data.

A just transition to climate resilience

The RRJ is designed to support regions and communities in a just transition to climate change, having integrated a range of principles, processes and practices that aim to ensure that no people, workers, places, sectors, countries or regions are left behind in the transition. As suggested by the IPCC (2022) regarding just transitions, it stresses the need for targeted and proactive measures to ensure that any negative social, environmental or economic impacts of economy-wide transitions are minimised, while benefits are maximised for those disproportionally affected.

The RRJ supports regions in co-designing their adaptation strategies with a participatory approach, recognizing the role that vulnerable populations play in a just transition. It will help regions in mapping the different stakeholders most exposed to the different climate risks and identifying the enabling conditions required to achieve the best possible future for all.

An iterative and multi-layered process

No transformation adaptation to climate resilience is linear. Allowing for experimentation and learning, and for iterations and evolution are critical. The RRJ is designed for multiple iterations – regions are encouraged to undergo parts of the journey and the journey itself multiple times, revisiting assumptions, learning from insights and stakeholder sentiment. Gaps in knowledge, data or finance will become apparent as different elements are explored or stakeholders engaged.

It will be of strategic interest then to undergo different iterations with different focus (such as by using different approaches or zooming into different sectors). It is advised that regions form cross-sectoral teams and to engage representatives from different departments.

Your journey:

Regions and communities are in the driving seat. The RRJ is there to support them in undertaking this journey, adapted to their situation as needed.

The RRJ should be applied taking into account the local context and build on what has already been achieved or is in motion. The RRJ should build on already developed strategies – revising and revisiting where relevant.

It is not necessary to use the RRJ as a whole new methodology, starting from scratch.

The RRJ approach ultimately provides the regions with the tools and methodologies to collect the necessary information to use the RRJ itself in the most strategic way possible, recognizing that the local stakeholders are often the most knowledgeable on their own needs.

Learning by doing:

The RRJ framework and its support structure will be improved over time building on the experiences from regions and communities that are applying it.

Koetz, T. and Arbau, L. (2023) A Guide to the Regional Resilience Journey (RRJ). Pathways2Resilience (P2R). Brussels.

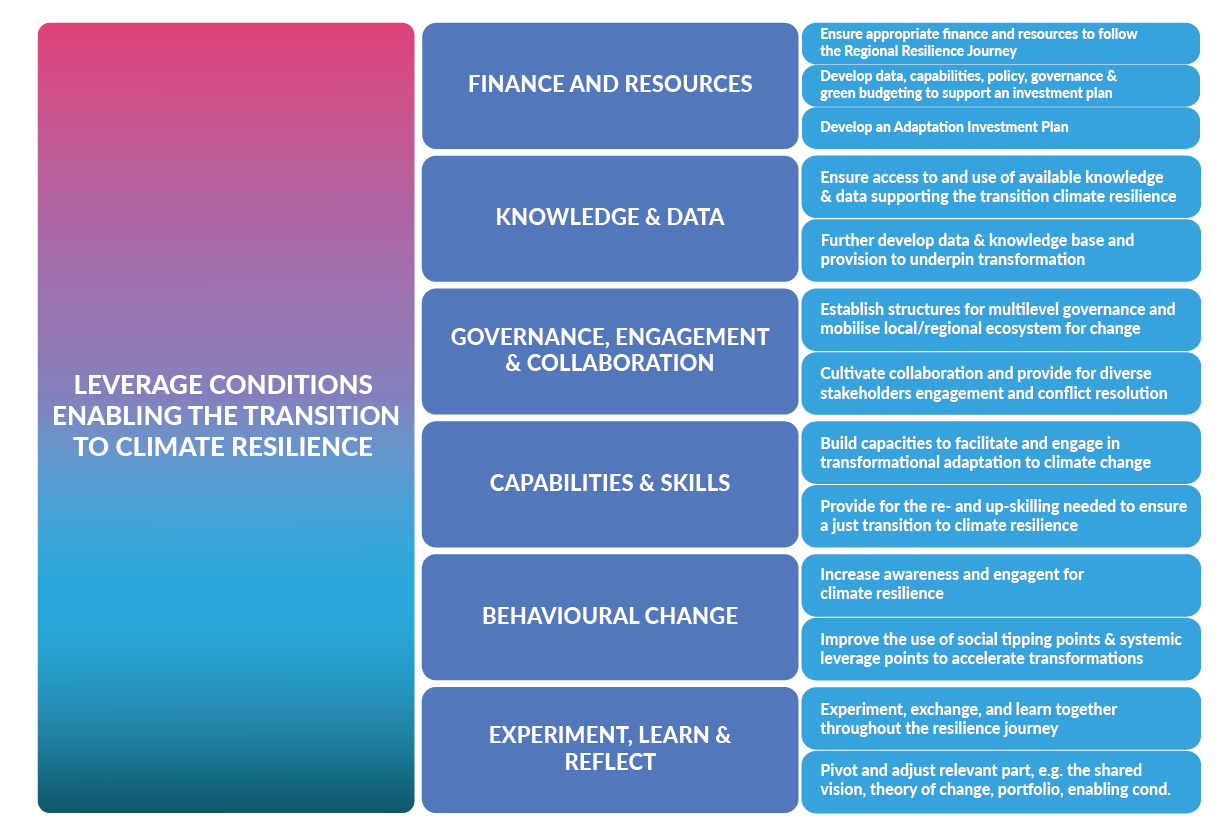

Leverage conditions enabling transition to climate resilience

In order to accelerate the transformation towards climate resilience, it is fundamental to leverage an enabling environment at the regional level for such change to happen. Because of the complexity of this task, it is impossible to plan for any social tipping point or transformation to occur. Instead, enabling conditions act as catalysts, smoothing the intricate process of change in multifaceted environments. They encompass a range of factors such as access to relevant knowledge and data, effective governance structures, meaningful stakeholder engagement, adequate financial resources, and capabilities and skills. They create an environment where ideas flourish, initiatives align, and efforts synergize. By strategically harnessing these conditions, transformative initiatives gain momentum and sustainability. Hence, any journey to climate resilience is not just about adapting to climate change; it is about leveraging these conditions to proactively shape resilient, thriving systems capable of withstanding the challenges of an ever-changing climate. It is important to establish and leverage enabling conditions from the beginning of the Regional Resilient Journeys on, and then to continuously uphold and further develop the enabling conditions throughout each step of the journey, all the way to having accomplished a just climate transition. As such, enabling conditions themselves should also be considered as areas for innovation.

There are many outputs stemming from the work leveraging conditions that are to enable the transition to climate resilience, e.g., stakeholder engagement or capacity building strategies, knowledge and data platforms, etc., but in most cases these could be seen as being integrated within the context of work done at different steps along the journey to climate resilience.

A critical output to highlight here in the context of the enabling conditions is the importance of developing a Climate Resilience Investment Plans and Pipeline of Bankable Projects.

Leverage finances & resources by developing an Adaptation Investment Plan

It is essential to ensure that appropriate finance and resources are leveraged to begin and progress throughout the Regional Resilience Journey. To actually implement transformational change, regions will need to mobilise finance and resources at scale, raising, deploying and repaying the associated capital. This involves ensuring public finance and budgeting approaches align with climate resilience objectives, and take a strategic approach, seeking to leverage and mobilise private finance (such as banks, pension funds, insurance companies and asset managers) . The European Investment Bank (EIB), Invest EU and the MIP4Adapt also play a pivotal role in bridging the financial gap and building technical capacity to regions The main way regions can mobilise the necessary finance is by developing an Adaptation Investment Plan and pipeline of bankable adaptation projects tailored to the regions’ needs and capabilities, in collaboration with actors across the region. The development and implementation of such a plan needs to be underpinned by approaches to develop the relevant data, skills, policy and regulation, governance, and budgeting approaches which enable finance to flow.

That means:

- Ensure appropriate finance and resources to follow the Regional Resilience Journey: To ensure appropriate finance and resources for the transition to climate resilience, a strategic approach is vital. Begin by securing approval to undertake the development of an Investment Plan, with the associated resources to undertake the activities. The P2R funding call can support regions in such resources.

- Develop data, capabilities, policy, governance, and green budgeting to support an Investment Plan: There are a wide range of data and knowledge, policy and regulation and governance, behavioural, financial and economic barriers which prevent finance from flowing into adaptation. The Resilience Maturity Curve framework identifies the capabilities regions need to develop and implement Investment Planning approaches and mobilise capital. This may include skills or knowledge, or green budgeting approaches. Similarly, developing an Adaptation Investment Plan will also identify wider actions with the regional government itself (e.g. policy reform, new governance) which may also be needed to implement the Investment Plan.

- Develop an Adaptation Investment Plan: Regions should follow the Adaptation Investment Cycle to develop an Adaptation Investment Plan. An Adaptation Investment Plan translates the high-level vision and pathways developed in the RRJ into bankable investments and supporting actions to implement them. It does this by:

- Generating a current baseline of Investment in Adaptation in the region,

- Identifying strategic barriers to adaptation finance,

- Defining Investment Needs,

- developing strategies to raise the finance for regions

- and if necessary, Matchmaking to develop bankable projects

The process results in an Adaptation investment Plan and pipeline of bankable projects in line with public financial management criteria and/or private sector requirements, such as compliance with the EU Taxonomy on Sustainable Finance. It also helps identify actions that will boost access to new sources and instruments and support implementation and delivery. Where needed, the approach also involves developing individual bankable propositions for areas identified as investment priorities but where further work is needed to secure investment.

Leverage knowledge & data

Decision-making relies on comprehensive, up-to-date, accurate, reliable and relevant information. Data supports risk and vulnerability assessment, highlighting inequalities and informing priority fields for investments. It illuminates potential solutions and precise actions data against climate-related threats. Moreover, accessible knowledge cultivates awareness, empowering communities and policy makers alike. It bridges gaps between research and practical application, fostering innovation and the sharing of best practices. Communities armed with relevant data can strategize effectively, mobilise resources efficiently, and respond resiliently to challenges. Ultimately, democratize climate-related knowledge and data fosters resilience. It can empower vulnerable communities and enable them to actively participate in shaping their resilient futures. Therefore, in the journey toward climate resilience, having access to and utilising relevant knowledge and data is not just beneficial but imperative, shaping effective, sustainable, and evidence-based climate actions.

That means:

- Ensure access to and use of available knowledge & data supporting the transition to climate resilience: To facilitate the access to knowledge and data and digital services that are critical for better understanding and managing climate risks, enhancing adaptive capacities and supporting transformative innovations, harnessing resources, and facilitate access to them. This can include climate data like the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), but also wider social and economic data, as well as local and community knowledge. Establish user-friendly platforms that seamlessly integrate C3S insights, making a continuous flow of updated information accessible to diverse stakeholders. Invest in data literacy and skill-building initiatives, empowering communities to interpret and apply information effectively. Collect disaggregated data and lived experiences of the most vulnerable to highlight power inequalities and social injustices. Foster collaborations between researchers, policymakers, and local communities, encouraging knowledge exchange. Additionally, promote open data policies to enhance transparency and collaboration. Regularly assess data needs, ensuring the information provided aligns with evolving resilience strategies and trends. By creating a seamless ecosystem where data is accessible, understandable, and applicable, societies can make well-informed decisions, driving effective climate resilience initiatives.

- Further develop data & knowledge provisions to underpin transformations: Embrace cutting-edge innovations like digital twinning, data spaces and AI, creating dynamic platforms for seamless data access and analysis. Integrate citizen engagement, empowering communities to actively participate in data generation. Explore collaborative design processes for digital knowledge services, ensuring user-friendly interfaces that enable meaningful contributions. Foster partnerships between tech innovators, citizens, and scientists, cultivating a collective intelligence approach. Disaggregate existing data by combining quantitative and qualitative information and approaches. By merging technological advancements with citizen empowerment, we foster a robust ecosystem where diverse insights converge. This convergence not only amplifies data accuracy but also ensures that societal actors play a central role in shaping resilient futures, driving transformative climate initiatives from the ground up.

Leverage governance, engagement and collaboration

Multilevel, integrated, cross-sectoral, and deliberative governance and collaboration, alongside meaningful stakeholder and citizen engagement, are essential cornerstones for accelerating transformations towards climate resilience. Multilevel governance ensures coordination and synergy across local, regional, and national levels, facilitating cohesive climate strategies. Cross-sectoral collaboration taps into diverse expertise, fostering innovative, interdisciplinary solutions. Deliberative governance promotes informed decision-making through inclusive, participatory processes, ensuring diverse voices are heard. Meaningful engagement of stakeholders and citizens fosters a sense of ownership, driving community-led initiatives and enhancing social acceptance and compliance. Considerations should also be given to changes needed in existing governance systems, e.g., with regard to the prevailing economic paradigm. By integrating these approaches, resilience efforts become comprehensive, addressing the intricate challenges of climate change.

That means:

- Establish structures/mechanisms that allow for cross-sector and multilevel governance and mobilise local and regional ecosystems for change: Establishing structures for cross-sector and multilevel governance while mobilizing local and regional ecosystems for change requires strategic planning. Start by fostering partnerships between government bodies, private sectors, and community leaders, encouraging shared responsibility. Establish coordination mechanisms and clarify internal roles and responsibilities tailored to the size and capacity of your regional or local authority (including human and technical resources) that facilitate cross-sectoral and multi-level decisions. Develop clear communication channels to facilitate seamless information exchange. Empower regional organizations and local communities with decision-making authority, ensuring initiatives align with specific needs. Continually identify and foster the participation of a plurality of actors, independently from their gender, race, economic capacity, physical and mental ability, sexual orientation, etc. Include traditional and non-traditional collaborators (civil servants, politicians, regulators, funders, researchers, journalists, artists, activists, entrepreneurs, companies, unions, educators, citizens, etc.). Also foster social innovation and citizen science, empowering individuals to take action in their own communities. Promote innovative learning and teaching methods, integrate i.e. citizen science, social innovation or action-oriented learning in educational activities and enhance the visibility of existing innovative programmes and initiatives for education and learning.

- Cultivate and nurture collaboration and provide for diverse stakeholder engagement and conflict resolution: Strengthen relationships between actors in the ecosystem. Build and maintain trust. Trust-based, collaborative relationships across a local ecosystem are essential to be able to take difficult decisions, concerted actions and stay on course over time. To enable these relationships to develop over time, hold and curate space – physical, digital, and otherwise – in which stakeholders from across the ecosystem can begin to interact and collaborate. Cultivate and nurture collaboration built on shared, distributed leadership toward the climate resilience goals. Collaboration requires regions to invest in the conditions, the settings, and spaces in which a plurality of actors can engage, learn and collaborate. Such conditions aim to foster a culture of shared purpose, participatory governance, and distributed leadership in alignment with expectations and efforts. Create and nurture opportunities for relationships to develop between diverse people, organisations, and institutions. Enable connections between those whose experience, imagination and understanding of problems differ from those most commonly involved in decision-making. Practise deep listening and address conflicts: Disagreements happen and conflict may occur. Recognise and validate the experiences, fears and determination that underpin each other’s convictions and make this a source of visioning. Demonstrate how to thoughtfully propose and accept compromises that serve the ecosystem’s shared understanding and vision.

Leverage capabilities & skills

Investing in spaces, where learning and skills building can happen, strengthens regions and communities to design and lead their own transformational change processes.

As the transition towards climate resilience evolves and action is taking place, the diverse actors in the ecosystem will be dealing with complex and evolving challenges, but also with potential windows of opportunity. It is hence important to create the conditions and promote spaces for stakeholders across the ecosystem to exchange, learn, reflect and work together on their challenges and opportunities.

Up-skilling ensures existing professionals adapt to evolving demands, enhancing their ability to implement innovative solutions. Re-skilling aligns the workforce with sustainable practices, creating employment opportunities within the climate resilience sector. By empowering individuals and communities with relevant skills, a capable workforce emerges, capable of driving transformative, equitable initiatives. This approach not only strengthens local economies but also ensures that climate resilience efforts are just, inclusive, and socially sustainable, benefiting all members of society.

That means:

- Build capacities to facilitate and engage in transformational adaptation to climate change: Engage with local leaders and stakeholders to map the available and missing skills to enable a resilient transformation. Invest in capacity-building programs to enhance their skills, enabling them to drive transformative initiatives effectively. Create shared, safe spaces and conditions for interaction, dialogue and experimentation with existing change-makers from across the local ecosystem. This can help these actors reflect, manage conflicts, dilemmas, stagnant situations, power dynamics and tensions as they continue their efforts. Create a fertile environment for new ideas, supporting and enabling the development of new individual and organisational capabilities as well as catalysing bottom-up social innovations. Foster creativity, exploration, co-creation, collaboration and facilitate the integration of multiple perspectives into transformative action with social innovation.

- Provide for the re- and up-skilling needed to ensure a just transition to climate resilience: To ensure a just transition to climate resilience, regularly conduct needs assessments to identify skill gaps within communities and sectors. Develop tailored training programs and collaborate with educational institutions and vocational training centres, aligning curricula with the demands of emerging green jobs. Prioritize inclusivity, ensuring marginalised communities have equal access to training opportunities and mentoring. Provide financial support, scholarships, and incentives to encourage participation, especially for underprivileged individuals. Foster mentorship programs connecting experienced professionals with newcomers. By investing in re- and up-skilling initiatives, societies empower individuals, fostering expertise that drives a just and equitable transition to climate resilience.

Leverage behavioural change

To leveraging behavioural change, both at the individual and systemic levels, increasing awareness about climate impacts is foundational, instilling a sense of urgency among individuals. Understanding and harnessing social tipping points, where small changes trigger significant shifts in collective behaviour, becomes a powerful tool. Similarly, identifying systemic leverage points—key areas within complex systems where interventions can create substantial impact—enables strategic, large-scale changes. By encouraging individual mindfulness and strategically targeting societal behaviours, regions can catalyse a domino effect, accelerating transformative changes towards climate resilience. This comprehensive approach not only empowers communities to face climate challenges but also positions regions as pioneers in driving impactful, sustainable adaptation efforts.

That means:

- Increase awareness and engagement for climate resilience: Increasing awareness and engagement for climate resilience on both individual and systemic levels demands a multifaceted approach. Start by disseminating accessible, science-backed information through educational campaigns, highlighting local climate risks and tangible solutions. Foster dialogue through community events, encouraging conversations about climate challenges and shared responsibilities. Empower individuals with practical knowledge, demonstrating how their actions impact resilience. Simultaneously, engage policymakers, businesses, and institutions, advocating for sustainable practices and policies. Utilize social media and interactive platforms to amplify messages, reaching diverse demographics. Establish partnerships with schools, NGOs, and local organizations, integrating climate education into curricula and community activities. By weaving awareness into the fabric of society, fostering dialogue, and embracing collaboration, a foundation for behavioural change towards climate resilience is laid.

- Improve the use of social tipping points and systemic leverage points to accelerate transformations: Understanding and harnessing social tipping points and systemic leverage points are instrumental in accelerating transformative changes towards climate resilience. Social tipping points represent moments when small behavioural changes trigger widespread adoption of sustainable practices. Identify these triggers through community engagement and research. Systemic leverage points, pivotal areas within complex systems, offer substantial impact. Analyse these points through systems thinking, targeting interventions where they yield maximal results. Collaborate with experts and stakeholders, utilizing their insights to pinpoint effective strategies. By strategic interventions at these critical junctures, transformative shifts can be catalysed, propelling communities and systems towards enhanced climate resilience.

Leverage experimentation, strategic learning & reflective adjustment

Leveraging continuous experimentation, strategic learning, and reflective adjustment of strategies and plans is pivotal throughout the regional resilience journey. Experimentation fosters innovation, allowing regions to pilot diverse approaches while learning in that process. Sensemaking as a practise aims to facilitate continuous learning and adaptation and generates valuable insights. This learning contributes to improved decision-making and more effective strategies. This needs to be based on a robust Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) framework providing a structured approach to measure effectiveness, enabling evidence-based decision-making. Reflective adjustment integrates lessons learned, refining theories, plans and strategies in response to evolving challenges.

That means:

- Experiment, exchange, and learn together throughout the resilience journey: To accelerate transformative changes towards climate resilience, regions must foster a culture of experimentation, exchange, and collaborative learning. Regions must deliberately create a culture and the space for experimentation, encouraging the testing of innovative approaches to climate challenges as well as accepting and learning from their failure. Establishing spaces for insights generation and knowledge exchange allows regions to promote collective learning and effective action, enhance understanding and dialogue, decision-making and helps driving systemic change in complex and dynamic environments. Concurrently, developing a robust Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) framework is essential. Reflecting the agreed Theory of Change, this structured approach enables systematic assessment of experiments, offering insights for refinement. By experimenting collaboratively, sharing experiences, and utilising a solid MEL framework, regions can adapt swiftly, enhancing resilience strategies and ensuring a collective, informed response to the intricacies of climate change.

- Pivot and adjust relevant parts, e.g., the shared vision, theory of change, pathways, enabling conditions: Regularly pivot and adjust key components of the Regional Resilience Journey like the shared vision, theory of change, pathways, the portfolio of interventions, and enabling conditions. Continuous monitoring and assessment of these elements against evolving climate challenges and emerging knowledge are crucial. Engage stakeholders in ongoing dialogues, integrating their insights for dynamic adjustments. Foster a culture of adaptability and openness to change, enabling quick response to new information. Embrace feedback loops and data-driven decision-making, ensuring strategies remain effective. By fostering flexibility and a willingness to pivot, regions can stay ahead, ensuring their approaches are agile, relevant, and responsive in the ever-changing landscape of climate resilience.

Coming soon

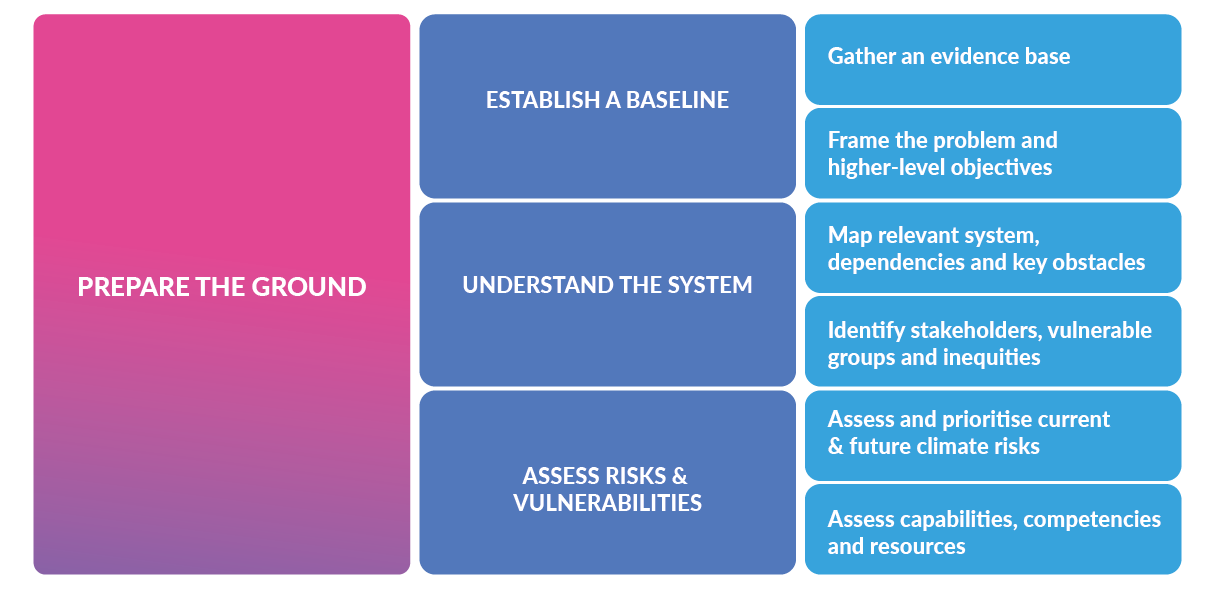

Prepare the ground

This first phase of the Regional Resilience Journey is to ensure regions situate their adaptation planning within the wider policy, social, environmental, economic and fiscal context for an initial framing of the scope, challenges and opportunities of the regions’ journey to climate

More concretely, this phase is about reviewing available knowledge of climate impacts and existing political commitments, regional policy, plans and strategies currently in place to address them; understanding who are the actors and stakeholders relevant in the climate adaptation context and their roles, vulnerabilities and capabilities; understanding the socio-economic context and dynamics, what are key resources available, important relationships and how they influence current developments, and ; and providing evidence for a reflection about regional priorities and opportunities for sustainable and climate resilient development.

Preparing the ground also means setting up and/or strengthening key enabling conditions that need to be leveraged for transformational change to happen. At this stage, this includes first and foremost those conditions that enable the development of the Climate Resilience Strategies and Action Plans themselves, such as relevant governance and stakeholder engagement mechanisms supporting decision making; and access to the needed resources and knowledge underpinning the planning process for such transformational climate resilience strategies to be developed. At the same time, regions should start thinking about how to strengthen the wider conditions that need to be in place to enable the transformations to climate resilience to unfold. This includes for example the capacity to mobilise the financial needs to implement the strategy, mechanisms to ensure that a just climate transition such as conflict-resolution mechanisms and up-and re-skilling programmes, etc.

By preparing the ground, regions will have the basic information on their climate vulnerabilities and risks, a first understanding on the enabling and hampering conditions to their resilience, as well as a knowledge on the ecosystem of actors to engage with for refining the diagnosis/evidence base. They will also have mobilised the necessary resources and knowledge and enabled a co-creative environment for the development of the Climate Resilience Strategies.

The output of this phase could be envisaged as a baseline report. This baseline report could cover key elements of the ‘preparing the ground’ phase, including in particular:

- An assessment of current and predicted future climate risks and vulnerabilities, including a prioritisation of key and most urgent risks and vulnerabilities;

- An assessment of adaptive capacities, competences and resources relevant for achieving a just transition to climate resilience, including a list of needs that should be addressed as a matter of priority, e.g. with regard to key enabling conditions;

- A systems map relevant to the transition to climate resilience, including a context or cluster analysis identifying relevant policies impacting climate risks and regional resilience maturity;

- A map of stakeholders, vulnerable groups and inequities, including a stakeholders assessment matrix mapping the interest and influence of each target group, thus their impact in regional resilience; a stakeholders’ profiling to identify their mandate, field of action and strategic interrelations; an influence map to scope out the impact of the project in the regional communities;

- Any indicators, monitoring frameworks (sectoral or hazard specific) that are developed by the regions. In addition, regions can include any learning approaches adopted to review adaptation progress.

Establish a baseline

At the beginning of the journey, it is important to establish a baseline that takes stock of where the region stands in terms of its climate risks, vulnerabilities, key challenges and opportunities, as well as the policies, regulatory frameworks and resources already in place to address these. Based on this stocktaking, and in parallel with gaining a good understanding of the relevant system(s), actors and resources (step 1.2.), regions should formulate an initial direction in terms of its problem framing and key adaptation objectives as it journeys towards climate resilience. This is important as it helps to mobilise relevant actors and guide preparatory activities, as well as informs the initial specification of a monitoring framework to assess any progress made on the regional resilience journey, over time.

That means:

- Gather an evidence base: Collecting and reviewing available information is a key step to understanding regional strengths and weaknesses, as well as barriers to building climate resilience and the specific environmental, financial and social systems. Regions will collect available data and information about: the regions’ profile (including the social, economic, environmental, infrastructural and meteorological context), its current and future climate risks (as far as available), as well as an estimation of the economic and non-economic losses suffered due to extreme weather, and the existing policies and regulatory frameworks relevant for climate adaptation and resilience.

- Frame the problem and higher-level objectives: Based on the preliminary evidence gathered, a range of relevant regional actors (informed by the stakeholder mapping in step 1.2.) will discuss and agree on an initial framing of the problem. The focus of this discussion will be to create and/or increase a common multi-stakeholder awareness of the general situation regarding the region’s climate risks and the regional resilience maturity level. This exercise will be key to collectively set the higher-level agenda for the region’s resilience journey. These again are an important step in guiding the understanding of relevant systems (step 1.2.), a deeper assessment of risks and vulnerabilities (step 1.3), and the co-creation of a vision (phase 2).

Understand the system

Begin by understanding all relevant aspects and parts through a systems thinking lens trying to make sense of the complexity of climate resilience by looking at all relevant parts and relationships as parts of a greater whole rather than by splitting them into separated parts. Understanding the challenge at hand from multiple perspectives and learning from past actions has real potential to accelerate and improve the impact of climate adaptation efforts. The issues regions and communities face in adapting to climate change are not straightforward, so uncovering the barriers that could block necessary changes is crucial to enable transformation. This means moving across value chains, sectors, and scales, from the micro to the macro to uncover key interdependencies between challenges. It also means to actively engage stakeholders across the region in an honest collective reflection on the successes and challenges of climate adaptation action so far.

That means:

- Map relevant system(s), their relations, dependencies and key obstacles: Map the at play regarding climate resilience (e.g., governance and regulatory systems (multi-level and cross-sectoral), technological systems, ecosystems, economic sectors, social initiatives, or behavioural pattern) to facilitate a strategic understanding of their causal relationships, dependencies, and key barriers and obstacles. Such regional metabolism scheme will be important for choosing the most impactful pathways, to overcome detrimental path dependencies and to avoid maladaptation. This systems mapping is built and improved over time (e.g., it will guide and be further improved by the more in-depth assessment in step 1.3.) and can take many forms from building pictures of governance frameworks or stakeholder engagement to quantitative modelling of flows within value chains or between urban and rural systems. The success of this process relies on the ability to ask the questions that reveal the dynamics of the systems at play: what the barriers are to change, local strengths and opportunities, interdependencies, resource flows and risks, including of cascading effects of climate impacts. Including relevant stakeholders ( , public and private actors) in the process enables a more comprehensive analysis, decreases the possibility of dissent, and just process.

- Identify stakeholders, vulnerable groups and inequities: Based on the mapping of systems, regions can undertake an analysis of relevant stakeholders, vulnerable groups and inequities. Mapping actors and stakeholders and their networks relevant to the climate resilience transition in the region will help to effectively mobilise them in the necessary co-creation processes along the region’s journey to resilience. Key here is to also capture the political economy of involved actors, e.g., who is supportive of, who resisting certain measures, and their power positions. Particular attention should be given to vulnerable groups and existing or possibly emerging inequities, as climate impacts are not only not evenly felt geographically, by income or over time, but adaptation options could possibly even widen such inequalities. This work will be key to ensuring a just climate transition. It will allow for opportunities for optimising resilience action by involving different interested people, but also by encouraging alignment with existing climate change adaptation and resilience initiatives and building on successful practices (avoid duplication of efforts while leveraging resources efficiently). In addition, this identification of stakeholders should be inclusive and participative, and is work that will be built and improved over time, e.g. after a more in-depth assessment of vulnerabilities under step 1.3.

Assess risks & vulnerabilities

To further prepare the ground for building a shared vision of a climate resilient future and developing the pathways towards that future, it is important to assess climate change risks and vulnerabilities, and opportunities, taking into account the systems’ mapping and their interdependencies to also account for cascading effects. Climate risks depend on three different factors:

The Regional Resilience Journey is focused on empowering regions to lead their own transition to climate resilience. As such, it places particular emphasis on regions’ anticipatory, adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities and related resources. Assessing these in sufficient detail is an important part to leveraging the enabling conditions in the most effective and efficient way possible.

That means:

- Assess and prioritise current & future climate risks: Building on the initial baseline and the mapping of the systems, the detailed assessment of social, environmental and financial risks and vulnerabilities is a key moment of reflection to develop a common understanding of the magnitude of the main climate threats to which the region is exposed and to identify those elements which must be protected and towards which action should be prioritised. In this context, it is important to consider as well key structural changes from climate mitigation and wider socio-economic change. For example, some economic sectors will be very different, some infrastructure will be profoundly different, alongside a different population. These can give you very different risk profiles. Acknowledging that climate change increases risks and impacts over time, such an assessment should also include predictions of future climate risks, and should be updated periodically, specifically after defining the vision and when defining pathways.

- Assess capabilities, competencies and resources: Building on the initial resilience maturity self-assessment as well as the mapping of stakeholders, vulnerable groups and inequities, a more detailed and cross-sectoral assessment of capabilities, competencies and relevant resources for achieving a just transition to climate resilience will be undertaken by the regions. This assessment will be structured according to the Key Enabling Conditions identified as most relevant for adaptation work. Having a good understanding of these and where strengths and critical challenges may lie, is important for focused efforts in leveraging and strengthening key enabling conditions that allow the regions to lead their own transition to climate resilience.

Coming soon

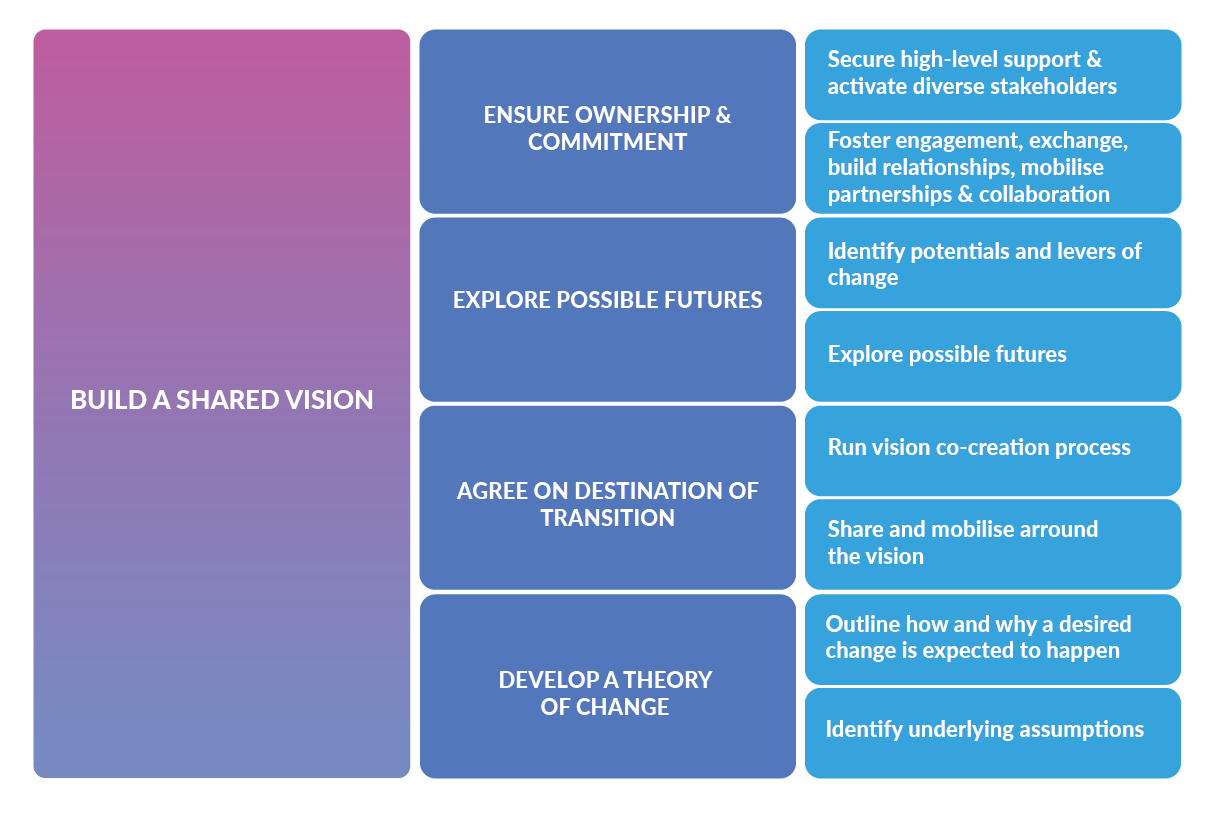

Build a shared vision

A critical step of the journey to climate resilience is co-developing a shared vision with stakeholders to work towards. Meaningful and active engagement of relevant actors in the process of building a shared vision is key to creating ownership of and commitment to the process and the vision itself. Exploring possible future scenarios generates positive narratives and leads to a shared understanding of what a just climate transition should entail for the region, while identifying regionally specific potentials and levers of change. The co-created vision will serve both as a mobilizing tool and a reference to keep the regional stakeholders accountable.

The output of this phase could be envisaged as a climate resilience strategy. This climate resilience strategy could cover key elements of the ‘building a shared vision’ phase, including:

- A shared vision of the climate resilient future that the region wants to achieve, including a theory of change outlining how and why a desired change is expected to happen and what are relevant underlying assumptions.

- A co-developed stakeholder engagement strategy & participatory design process, including the description of (to be) established engagement mechanisms and structures (see ‘leveraging enabling conditions’). The stakeholder engagement strategy should be revisited once a shared vision is established and pathways for the transitions have been elaborated.

- An overview of identified regional transformation potentials and possible climate resilient futures, as well as of key levers of change and enabling conditions that regions and communities would need to address.

Ensure ownership & commitment

Meaningful and active involvement of relevant actors in the process of building a shared vision is key to creating ownership of and commitment to the process and the vision itself. In line with and supported by plans to leverage cross-sectoral and multilevel governance, as well as the meaningful involvement of stakeholders and citizens, in particular of vulnerable groups, ownership and commitment are ensured by the appropriate activation of stakeholders and facilitation of exchanges, and the mobilisation of partnerships and collaborations. While this is an important aspect across the entire journey, it is of particular importance to the building of a shared vision.

That means:

- Secure high-level support & activate diverse stakeholders: Secure high-level support by creating a favourable political situation for the transition to climate resilience. Reference could be made to relevant legal obligations, policies, strategies, or plans at higher or lower levels of governance such as National Adaptation Plans or strategies, the EU Adaptation Strategy, the EU Mission on Adaptation to Climate Change, and the EU Floods Directive, or Community/Local Adaptation Strategies. Data collected in the baseline report [hyperlink] will support an evidence-based argument for the need to embark on a transformation pathway. Contact stakeholders and raise awareness about the regional resilience context, the implications and commitment to a resilient transformation and the opportunity for them to be involved in the process and influence regional development. Informative sessions and co-created workshops will serve to facilitate coordination and decision-making.

- Foster engagement, exchange, build relationships, mobilise partnerships & collaboration: Purposefully build relationships based on common resilience-focused interests and objectives, building on the common interest and agendas mapped in step 1.2.2 [hyperlink]. The process of transformation towards a more resilient regional context depends as much on informal relationships and networks as it does on formal structures, resources, and processes. Nurture the development of new collaborations, new relationships of trust, and new networks for partnerships and alliances. Create participatory mechanisms supporting the regional resilience journeys where stakeholders are part of the decision-making process at multiple points in time. Co-develop a strategy for engagement of relevant actors (including businesses, citizens’ groups and public entities), detailing who to engage in the process, when and how, including specific objectives of collaboration, roles and a draft timeline of engagement activities.

Explore possible futures:

Exploring possible futures is pivotal in taking decisions which collectively shape a region’s transition to climate resilience while recognizing the inherent climate and socioeconomic uncertainties we face. By envisioning diverse scenarios, including of smooth or abrupt transitions, we gain invaluable insights into what a just climate transition means for different people, as well as the complex interplay of factors shaping future climate resilience. It also allows opening stakeholders and actors to the possibility of creating new futures, and exploring their roles in that process. These explorations offer a nuanced understanding of regional dynamics, enabling regions to craft tailored, flexible and robust strategies. Understanding specific potentials equips regions to harness local resources effectively, while recognizing levers of change allows them to navigate transitions smoothly. These insights not only present varied choices but also offer compelling narratives crucial for engaging society in the transition to climate resilience.

That means:

- Identify potentials and levers of change: The exploration of future scenarios starts from the identification of the various potentials and opportunities and of levers of change that a region might have for (economic, social and environmental) transformation potentials that an adaptation to climate change could bring to the regions. Exploring various levers of change (mechanisms or strategies for change such as technology; governance, policy and regulation; finance and business models; culture, citizen participation and social innovation; capacity and capability building), and how they could possibly be deployed to reach different climate resilience results is also crucial. Also part of this exercise could be considerations on defining (new) common goods, moving out of traditional ‘secure’ decision making system to enable (legally & technically) experimentation, or emphasising methodologies such as back-casting, or the work on new metrics. This work will form an important building block to developing a Theory of Change (step 3.1.) how a shared vision of a climate resilient future (step 2.3) can be reached.

- Explore different possible futures: Before coming to a shared vision of a climate resilient future, it is important to explore different possible futures, exposing important trade-offs and value decisions to be made. Regions can use existing baseline evidence identified in previous steps to develop different possible climate resilient futures to help illustrate whether various starting points – or levers of change – and policy mixes create plausible pathways towards transformation and transition.

Agree on ‘destination’ of the climate resilience transition

Fostering a shared vision within a diverse ecosystem is a vital step towards creating a cohesive narrative and a clear sense of purpose and direction. This endeavour involves active engagement with stakeholders across the ecosystem to gauge the extent of their aspirations, contemplate various avenues, and identify potential challenges. By collaboratively crafting a new narrative, grounded in the collective insights and intentions arising from this inclusive process, a profound understanding and ownership is cultivated. This shared perspective not only expands the realm of what is perceived as achievable but also underscores the essential actions required within the local ecosystem.

That means:

- Run a vision co-creation process: Stakeholders are invited to take part in a priority setting exercise, based on the social and ecological constraints identified so far. Through different approaches (including creative, somatic, deliberative and intellectual exercises), a representative group of citizens will be able to generate positive perspectives on the co-benefits of climate action with the whole ecosystem, rooted in realistic future scenarios. This process serves to build stronger connections and unite stakeholders, embracing their diverse perspectives and challenges. Actors can align their efforts to the development of the common vision for the regions’ future.

- Share and mobilise around the vision: Run a social activation campaign to share and validate the outcome of the visioning process within the region. Collect commitments from the different stakeholder groups necessary to implement the vision, ensuring the whole region is aware of the collective action needed. Language should be simple, visual, relatable and concrete – thus, understandable by all to spur all towards collective action.

Develop a theory of change

A Theory of Change (TOC) provides a structured framework to understand the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of the changes needed to deliver the regions’ vision across systems, sectors and stakeholders. It dissects the web of cause-and-effect relationships, delineating how, why and when each action can contribute to the desired transformation. Crucially, it outlines the collective assumptions or beliefs that underpin these strategies, allowing for scrutiny and adjustment where necessary. A Theory of Change ensures a realistic and evidence-based approach, preventing misguided efforts and fostering adaptability; as well as enabling reflection and refining of strategies based on evolving insights.

That means:

- Outline how and why a desired change is expected to happen: Developing a Theory of Change for climate resilience involves a systematic analysis of cause-and-effect relationships, illuminating the pathways toward a desired outcome. Building on the identified transformation potentials and levers of change of the regions (step 2.2.1), and based on a comprehensive understanding of the systems, the current climate vulnerabilities and regional resources, capacities and dynamics (phase 1), a Theory of Change provides a logical framework, outlining why specific strategies are expected to yield desired outcomes and how the use of certain levers is to contribute to the broader goal of reaching the shared vision for the transition to climate resilience. This process incorporates stakeholder perspectives, scientific data, and contextual intricacies, ensuring a comprehensive approach.

- Identify underlying assumptions and indicators: Identifying underlying assumptions in a theory of change for climate resilience is crucial for effective planning and execution and allows for scrutiny and adjustment if necessary. Scrutinize each step and element, questioning implicit beliefs and presuppositions. Engage diverse stakeholders, encouraging them to critically assess the theory’s foundations and to validate assumptions under various conditions. This process not only enhances transparency but also guides resource allocation and evaluation efforts effectively. Rigorous data analysis and feedback loops are essential to validate or challenge these assumptions over the course of the region’s resilience journey. Regularly revisit and update assumptions as new information emerges.

Coming soon

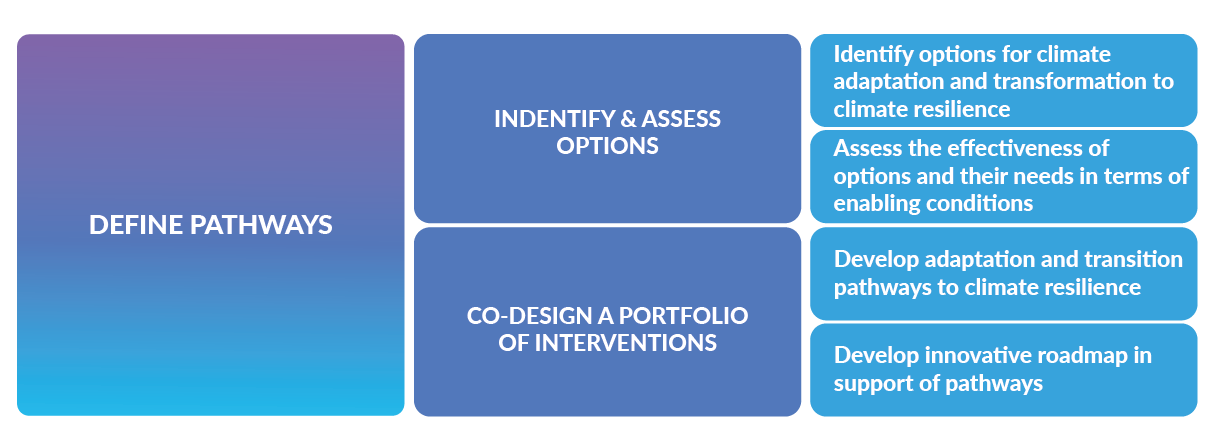

Define pathways

Pathways for climate adaptation and transitioning to resilience bring together interventions across multiple levers of change in a coherent portfolio of actions, outlining how each intervention contributes to progress towards the desired pathway. Pathways provide a structured and evidence-based decision-making framework to ensuring efforts align with the overarching shared vision and activities, outputs and outcomes are prioritised and sequenced over time.

Pathways need to be rooted in a theory of change that delineates how and why a desired transformation is anticipated to occur, while critically identifying underlying assumptions. Potential options and actions must be identified covering a broad range of levers of change. Finally, pathways must be drawn that include sufficient options to achieve the desired vision and transformative adaptation goals in a timely innovation agenda and portfolio roadmap.

A coherent portfolio includes visible early wins that mitigate risks as well as contribute to long-term resilience goals and desired wider societal transformation. Portfolios must balance these with uncertainty, including experiments to test innovative options that create insights for future decisions. This process needs to be supported by an iterative and continuously improving Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning framework.

The output of this phase could be envisaged as a climate resilience action plan. This climate resilience strategy could cover key elements of the ‘building a shared vision’ phase, including:

- A description of the adaptation and climate resilience transition pathways, for each outlining a portfolio of interventions drawn from a range of options for adaptation and transformation to climate resilience, including an assessment of the effectiveness of identified options and their needs in terms of enabling conditions

- An innovation agenda and a policy roadmap in support of pathways.

Identify & assess options

Identifying a variety of possible interventions for climate adaptation and transformation to resilience is key for assembling possible steppingstones for the pathways to regional climate resilience. It is important to diversify the approach, recognizing that a singular solution is insufficient given the complexity and uncertainties involved in climate challenges. Secondly, assessing these options against their capacity to deliver multiple resilience benefits and their effectiveness not only in building resilience but also fostering flexible and robust system transformation is vital. It allows us to discern their real-world impact and feasibility. Moreover, understanding the necessary enabling conditions for their positive implementation and what are further needs to achieve the desired transformation is essential. Guided by the Theory of Change, this analysis provides an overview of potential building blocks of the best possible portfolio of interventions, including insights into what works, why it works, and what resources and support structures are necessary for success.

That means:

- Identify options for climate adaptation and transformation to climate resilience: To construct a robust portfolio of interventions for the pathways to regional climate resilience, the identification of a wide and diverse range of possible actions or interventions is key. Begin by comprehensively surveying various climate adaptation and transformation options, recognising the multifaceted nature of climate challenges. Engage diverse stakeholders, tapping into local knowledge and global expertise. Explore a wide spectrum of adaptation options, ranging from nature-based solutions to technological and digital innovations, financial and social innovation and community-driven initiatives, and policy frameworks.

- Assess the effectiveness of options and their needs in terms of enabling conditions: Evaluating climate adaptation and resilience options demands a multifaceted approach. Firstly, assess their effectiveness to deliver multiple resilience dividends by scrutinizing real-world impacts on ecological, social, and economic domains, and possible synergies with other societal goals such as job creation, social equality, and human well-being. This is important as the co-benefits, or broader value proposition of adaptation options can often provide revenue streams which can contribute towards their financing. Rigorous data analysis, and case studies provide valuable insights. Secondly, identify enabling conditions crucial for these options to be implemented successfully, including their requirements regarding knowledge and data, governance and stakeholder engagement, capacity building and skills, as well as financial and other resources needs. Identifying actions that not only can have the greatest impact and create a pathway towards climate resilience, but that also those are the most viable, especially financially (for example, because funding is already available or because the actors of the city or region have the knowledge and capabilities to implement actions toward this pathway). This evaluation is to ensure that the options for climate adaptation and transformation to climate resilience are not only viable but also just, equitable, sustainable and bankable.

Co-design a portfolio of interventions

Developing pathways for climate adaptation and transitioning to resilience ultimately means co-creating a comprehensive portfolio of actions out of the identified and assessed options as well as an agenda of innovation actions underpinning these pathways to drive progress. The co-creation of a portfolio is an ongoing process that brings together existing policies, actions, and programmes with new or accelerated interventions in a set of transformative actions to achieve the shared vision. A portfolio of transformative interventions also compiles efforts across departmental silos and diverse stakeholders. It assembles a set of coherent initiatives which can strengthen each other and reinforce the connections between the multiple actors needed to co-design and enact such portfolio while minimising trade-offs. The portfolio co-creation process itself can help overcome obstacles and enable positive synergies. Ensuring the integration of the portfolio’s actions to create pathways for transformation, co-benefits and learning is challenging though and will require specific attention when taking action. The portfolio should be sequenced to ensure they effectively address risk (e.g., low regrets, climate smart, or adaptive planning), to meet local economic and political priorities, and ensure that they fit within the existing fiscal space, and public financial management requirements of a region.

Next to assembling pathways out of the identified and assessed options, a portfolio of interventions should also include the development of an innovation agenda or innovation roadmap that underpins and drives progress towards these pathways. Such innovation roadmaps are to encourage research, development, and implementation of cutting-edge technologies and methodologies. They inspire continuous improvement and adaptation, ensuring that the chosen pathways remain dynamic and responsive to evolving climate scenarios.

That means:

- Develop adaptation and transition pathways to climate resilience: In collaboration with relevant stakeholders, assemble the identified options into a cohesive portfolio of interventions prioritising options based on their urgency, relevance, effectiveness, and feasibility within the regional context. Recognizing that regional contexts differ and that a singular solution is insufficient given the multifaceted nature of climate challenges, and that integrated strategies cater to different vulnerabilities, all together promoting a holistic resilience. By embracing this diversity, the pathways also become dynamic, capable of adapting to evolving challenges. As such, pathways need to pay specific attention to barriers and synergies that may arise, as well as to the potential costs and benefits. Guided by the theory of change, clarify the expected early outputs of interventions sets, which will be the necessary conditions to achieve long-term outcomes. Clarifying this “impact logic” will help generate insights on which actions are working (or not), and for whom, to create a pathway to target. Exploring pathways to change assists the creation of the Action Plan and Investment Plan over time (including future iterations of these documents). This will avoid unnecessary data collection later and support continuous extraction of insights and learning. Having a clear and coherent understanding of how an impact pathway and its co-benefits would unfold will support regions in selecting the most useful indicators for Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) of actions. At this stage, regional stakeholders will need to reflect on which quantitative or qualitative data is required to evaluate whether actions are achieving the desired outcomes to unlock.

- Develop transformative innovation policy roadmap in support of pathways: To develop an innovation roadmap for climate adaptation and resilience, regions need to identify gaps and opportunities specific to their needs based on the previous assessment of current technologies and practices. More concretely, the region will create a list of actions that ensure new and innovative tailored local approaches to climate adaptation and resilience by involving researchers and other stakeholders. The region will demonstrate how its local actors can play a key role in co-creating new approaches to climate adaptation by identifying pilot cases. Prioritize research and innovation areas based on feasibility, impact, and sustainability. Establish clear milestones and timelines, ensuring accountability. Secure funding and resources to support innovation initiatives. Foster partnerships between academia, industry, and government bodies, fostering a supportive ecosystem. Regularly evaluate progress, adapting the roadmap as technologies evolve. This iterative, inclusive approach drives continuous innovation, enhancing climate resilience strategies.